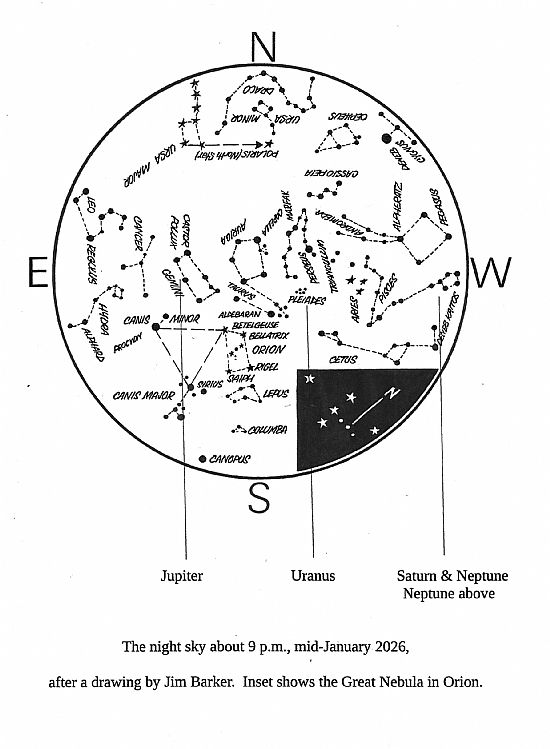

The Sky Above You, January 2026

by Duncan Lunan

The Moon was Full on January 3rd, still another 'supermoon' at its closest to the Earth, and appeared close to Jupiter that night. At the same time the Earth came to perihelion, its nearest to the Sun, so the Sun, Earth, Moon and Jupiter were not only at syzygy, all of them roughly in line, but also almost as close together as they can get. The following night the Moon grazes the top of the Open Cluster Praesepe, 'the Beehive', which on some old maps is drawn as the tuft on the tail of Leo. The Moon is New on January 18th and as a crescent, it passes near Saturn on the 22nd and 23rd. It passes above Jupiter on the night of the 30th-3lst. On the 27th it crosses the top of the Pleiades, occulting the stars Taygeta, Electra and Merope in that order as it moves eastward, all of them between 8.50 and 10.30 p.m.. The occultation of Maia can not be seen from England, but on a line from Fife to Bute, the star will graze the southern cusp of the Moon around 9.31 p..m..

The planet Mercury has now left the morning sky and is not visible from the UK in January, though it can be seen after sunset further south, e.g. from the USA. Mercury passes the Sun on the far side (superior conjunction) on January 21st.

Venus too is not visible in January, at superior conjunction on the 6th, and neither is Mars, at conjunction on the 10th.

Jupiter is brilliant all night in Gemini, rising near sunset, e.g. at 3.45 p.m. on the 10th, when it comes to opposition, due south at midnight, the night after its closest to the Earth. Astronomy Now points out that it will be visible for more than a Jovian day of 9 hours 50 minutes, so features on the right of the planet in early evening will reappear on the left before dawn. Nigel Henbest's annual guide Stargazing 2026 recommends looking for Jupiter's moons with binoculars or a telescope on the nights of the 15th, around 6 p.m., and the 29th, about 9 p.m., when the four large moons will be on the same side of the planet and arranged in order outward - Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto - making it obvious which is which. Before opposition their shadows will precede them in transit across the planet, and follow them afterwards; as always there are detailed predictions in the current issue of Astronomy Now. Jupiter was near the Moon on the 3rd and will be again on the 31st.

Another interesting snippet in that issue concerns the object now called 'Oval BA', lying south of the Great Red Spot and occasionally lapping it due to the planet's different rotation rates at different latitudes. It formed in the early 2000s from a merger of three of Jupiter's 'white ovals', so prominent in the Voyager spacecraft flybys of 1979, and then turned red, becoming the Little Red Spot for a time. When I was running the North Lanarkshire Astronomy Project in 2006 there was a lot of interest in it from school classes, because New Horizons had photographed it in close-up on its way to Pluto earlier that year, and the storm had turned white again. It's thought that the red colours of the largest spots are due to phosphorus compounds created by the action of solar ultraviolet radiation, at their slightly higher tops. Indeed, the Little Spot has now turned red once more, inside an orange ring.

Saturn, between Pisces and Aquarius, sets about 10 p.m., with the Moon nearby on the 22nd and 23rd. The rings are still very thin to our view, with a separation of less than a degree, but there are chances to see the giant moon Titan pass above them on the 9th and 25th. Titan will be hard

to spot because its shadow is no longer visible on the planet.

Uranus in Taurus, below the Pleiades, sets about 4 a.m., near the Moon on the 27th.

Neptune in Pisces is only three degrees above Saturn, also setting around 10 p.m.. and with the Moon nearby on January 23rd.

The Quadrantid meteors from comet EH1 peaked on the night of the 3rd, as the Supermoon reached its brightest, so there could hardly have been worse conditions in which to observe the shower, which is normally worth watching.

Comet 24P Schaumause is in the morning sky, tracking east-south-east through the constellation Boötes as it follows Ursa Major up the sky, but the Astronomy Now headline 'Comet Bright in the Pre-Dawn Sky' is a bit OTT because it will be below naked-eye visibility at 8th magnitude. Below Boötes in turn is the circlet of Corona Borealis, just below which the 80-year nova T Coronae Borealis is expected any time. I've never seen a nova and kept watch all last year to no avail, and Astronomy Now's headline for it is 'The Star that Won't Explode'. Nevertheless, a Happy New Year to all!

Duncan Lunan’s recent books are available through Amazon; details are on Duncan’s website, www.duncanlunan.com.

The Sky Above You

By Duncan Lunan

About this Column

I began writing this column in early 1983 at the suggestion of the late Chris Boyce. At that time the Post Office would allow 1000 free mailings to start a new business, just under the number of small press newspapers in the UK at the time. I printed a flyer with the help of John Braithwaite (of Braithwaite Telescopes) offering a three-part column for £5, with the sky this month, a series of articles for beginners, and a monthly news feature. The column ran from May 1983 to May 1993 in various newspapers and magazines, but never in more than five outlets at a time, although every one of those 1000-plus papers would have included an astrology column. Since then it’s appeared sporadically in a range of publications including The Southsider in Glasgow and the Dalyan Courier in Turkey, but most often, normally three times per year, in Jeff Hawke’s Cosmos from the first issue in March 2003 until the last in January 2018, with a last piece in “Jeff Hawke, The Epilogue” (Jeff Hawke Club, 2020). It continues to appear monthly in Troon's Going Out and Orkney News, with an expanded version broadcast monthly on Arransound Radio since August 2023

The monthly maps for the column were drawn for me by Jim Barker, based on similar, uncredited ones in Dr. Leon Hausman’s “Astronomy Handbook” (Fawcett Publications, 1956). Jim had to redraw or elongate several of them because they were drawn for mid-US latitudes, about 40 degrees North, making them usable over most of the northern hemisphere. The biggest change needed was in November when only Dubhe, Merak and Megrez of the Big Dipper, as the US version called it, were visible at that latitude. In the UK, all the stars of the Plough are circumpolar, always above the horizon. We decided to keep an insert in the January map showing the position of M42, the Great Nebula in the Sword of Orion, and for that reason, to stick with the set time of 9 p.m., (10 p.m. BST in summer), although in Scotland the sky isn’t dark then during June and July.

To use the maps in theory you should hold them overhead, aligning the North edge to true north, marked by Polaris and indicated by Dubhe and Merak, the Pointers. It’s more practical to hold the map in front of you when looking south and then rotate it as you face east, south and west. Some readers are confused because east is on the left, opposite to terrestrial maps, but that’s because they’re the other way up. When you’re facing south and looking at the sky, east is on your left.

The star patterns are the same for each month of each year, and only the positions of the planets change. (“Astronomy Handbook” accidentally shows Saturn in Virgo during May, showing that the maps weren’t originally drawn for the Hausman book.) Consequently regular readers for a year will by then have built up a complete set of twelve.

©DuncanLunan2013, updated monthly since then.